A four-part series

The rice we Filipinos eat isn’t all the same. Some are soft and sticky; their grains are either short or long and slender; and even their aromas differ. This is because their characteristics vary due to the traits combined through the process called rice breeding.

A tale unknown to many, one of the farmers’ hurdles is how to critically choose which rice variety to cultivate. Beyond its eating quality, they also assess the varieties based on their response to climate, resistance to pests and diseases, and other local conditions, which contribute to how their yield will succeed in the harvest season.

The Philippine Rice Research Institute and the International Rice Research Institute are the primary breeding institutions in the country. Seeds of many of the varieties they developed are being distributed to farmers under the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) Seed Program.

Every season, the Program provides rice farmers nationwide with free inbred certified seeds of varieties that have undergone intensive research and testing to ensure their quality and suitability. The initiative spares farmers from making do with home-saved seeds from previous harvests, which may have already lost their vigor and purity over time.

Since 2019, the RCEF Seed Program, with support from the DA-National Rice Program starting 2023, has been providing rice farmers with free NSQCS-approved Certified Seeds through the local government units. This program ensures that the product of years of breeding research and variety development is within reach of farmers and can influence their harvests.

“For the past six years of the program’s operations, nearly 20 million bags of inbred certified rice seeds were distributed to more than 2 million farmers all over the country,” RCEF program management office director, Dr. Flordeliza H. Bordey, reports.

She further revealed that, from the baseline of 3.63t/ha in the 2019 dry season, the yields of farmers who benefited from the program grew to 4.37t/ha in 2024; from 3.69 to 4.03t/ha in the wet season.

Farmers’ feedback on the seeds is documented and looped to help breeders refine and develop new varieties. This helps maintain a solid foundation for continuing breeding efforts by reinforcing the value of high-quality genetic materials.

Currently, over 300 rice varieties are available in the Philippines. This four-part story revolves around the reasons why and how these varieties were bred, the process, the impacts of rice science, and how it benefits Filipino farmers.

It takes 8-12 years to produce a new rice variety

The first step in breeding a rice variety is selecting the characteristics that the market demands, like drought tolerance.

Next is generation advancement, or repeated planting, to ensure that the characteristics incorporated into future varieties are uniform throughout the last generation. Normally, this procedure can take up to 5 years, but modern and rapid breeding approaches help breeders bypass the painstakingly long phase. It is also the phase where screenings and tests from various disciplines are conducted, including grain quality evaluation and response to pests and diseases.

“We would then proceed with the field testing and trials in our station to see their highest potential yields and pest tolerance under stressful environments. After four seasons or 2 years of planting in the station, we plant them in multiple locations to test if they are adapted to various climatic conditions throughout the country,” Christopher C. Cabusora, an active senior breeder at PhilRice, explained.

Eventually, the candidate varieties would undergo different tests under the National Cooperative Tests, Rice Varietal Improvement Group, and the National Seed Industry Council to examine their identity, integrity, and purity.

After 8-12 years, the process advances to seed multiplication and commercialization of an approved rice variety. Modern procedures such as high-throughput phenotyping and molecular tagging are employed in selecting traits. These advances can hasten breeding by up to two years.

To further validate the specific performance of the newly released varieties, they are tested across the different regions in the country through the DA—Regional Field Offices. They implement the on-farm Participatory Varietal Selection (PVS), which was renamed Participatory Performance Trial and Validation (PPTV) to know the location-specific adaptation of the varieties. Farmers’ preferences are featured in this process in terms of good agronomic performance and sensory evaluation. Moreover, it influences the recommendation domain of a particular variety whether for National or Regional level.

Cabusora explained that breeding should be continuous due to environmental changes. Droughts, floods, pests, and diseases are the major factors that shape the breeding of new varieties. He elaborated that pests and diseases usually evolve and make varieties lose resistance.

Seed production and commercialization

Before the variety is released and distributed to farmers, the master seeds generated from the breeding process are reproduced for further multiplication into nucleus and breeder seeds; eventually into foundation, registered, and certified seeds.

Planting the master seeds is quite different from planting ordinary seeds for food production. Under a technique called “panicle-to-a-row,” master seeds in a panicle are planted in a single row. If a row is seen with impurities, the entire row will be discarded. This is because the impurity will just reappear if the seeds are planted continuously. Harvest from master seeds becomes the nucleus seeds, from which Breeder Seeds will be produced and labeled with white tags.

The BPI-National Seed Quality Control Services (NSQCS) examines and certifies these seeds to be 100% pure. BPI-NSQCS is a regulatory body that certifies the seed classification of any variety based on a standard that differentiates Breeder Seeds (BS), Foundation Seeds (FS), Registered Seeds (RS), and Certified Seeds (CS).

When planting BS, breeders use a mechanical transplanter due to its large planting area. Harvest from this is distinguished as FS, which bears red tags. From these seeds, RS are produced.

The RS, which has green tags, is sold and distributed to accredited seed growers. Harvest from registered seed is called CS, which farmers plant to produce commercial palay for milling.

CS with blue tags are of high quality, purity, and germination rate, which contribute to higher yields. Seeds that are planted repeatedly may not be as efficient and pure as CS.

Rice breeding is public service

Hilario C. Dela Cruz, now 86, spent 12 years of his entire professional life breeding a new variety of rice that could withstand cold temperatures in the highlands of Ifugao and Benguet, with the goal of helping them achieve rice food security. Yet, when the newly developed rice variety was introduced, the Cordillerans had difficulty adopting it.

According to Dela Cruz, the traditional rice variety (TRV) that Benguet farmers cultivate could only yield 1t/ha, which could hardly feed their families. The hopes of his team were high as they successfully bred a cold-tolerant variety that could yield 4t/ha.

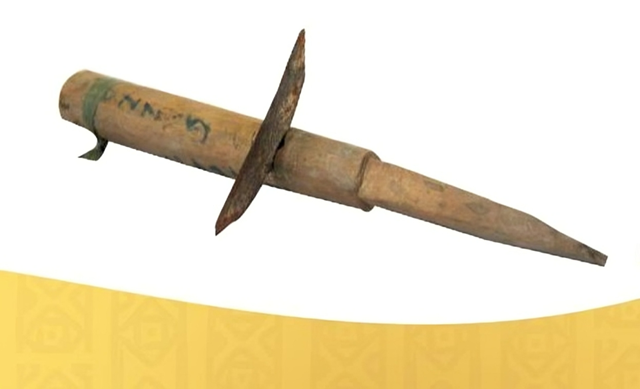

However, the physical characteristics of the high-yielding variety (HYV) developed vastly differed from those of the heirloom rice or TRV. For example, the flag leaf (topmost leaf) of the TRV is horizontal, making the panicles easier to harvest with the use of their “rakem,” a finger knife. In contrast, the flag leaf of the HYV is erect, making harvesting panicles more laborious.

The flag leaves are detached from the straw before the panicles are bundled into the desired size for drying. One bundle, when pounded, would yield rice enough for one family meal.

“Naugaw or wasteful, the Ifugao farmers described reaping the crop using a scythe (karet),” Dela Cruz added. The rakem harvests panicles one by one.

Harvesting Ifugao’s tall traditional varieties using the rakem prevents shattering and minimizes grain losses.

A 2017 study documented that rice crops flattened by strong winds and heavy rains are best harvested by using the finger knife. The bundled panicles are easier to haul from the terraced fields to storage areas or to hang over firewood stoves to dry for eventual pounding.

“We learned from that experience. It requires 10-12 years to breed a variety. You should set objectives and consult farmers if you want a variety that would be helpful to them,” he asserted.

Dela Cruz lamented that they are proud of what they breed, but the farmers, at times, may not find it useful. After all, breeding should not be a one-way but an intercultural act of public service.

In response to the challenge, their breeding program was recalibrated based on market segments—a combination of farmer, consumer, and seed grower preferences, along with market demand and the rice-growing ecosystem in mind. They have also started conducting technology demonstrations of upland rice varieties for farmers to witness their performance.

Passing on the mission

Twenty rice varieties after he retired, this lesson did not lose its essence. It was passed on to his juniors, embodied by Thelma F. Padolina, his mentee.

In turn, she successfully bred NSIC Rc 160, one of the most sought-after varieties among farmers and well-loved by Filipino consumers. It is a nationally recommended and regionally preferred variety.

NSIC Rc 160 averages 5.6t/ha and maximum of 8.2t/ha. It is resistant to various rice pests.

More than anything else, it has a soft grain texture when cooked because of its low amylose content, which Filipinos love. Padolina boasts that even agriculture students from Generation Z still know and favor this rice variety.

Woman behind Rc 160

While the average attention span is only eight seconds nowadays, rice breeders like Thelma Padolina found solace in waiting for 12 years to produce a rice variety that Filipinos will plant and eat.

She is one of the most decorated rice breeders in the Philippines. In 2014, shortly before she retired, Thelma won the International Senadhira Rice Research Award given by IRRI in Bangkok, Thailand.

Padolina, now a consultant breeder at 75, began her career as a seed analyst, where she certified seeds at the then BPI-Maligaya Rice Research and Training Center (MRRTC). A chemist, she was always fascinated with the process of rice breeding in a laboratory near their office.

“In the selection of seeds, in the process of crossbreeding, the work they did in the greenhouse, I always tagged along,” she admitted. The head of the agronomy office, where rice breeders then worked, didn’t favor women.

“At that time, lady breeders were discounted due to their menstrual period and were thought to be incapable of descending to the muddy rice fields,” she recalled.

Despite this, she paved her way and learned the science of rice breeding from her peers. She kept on participating in hands-on laboratory activities and asked numerous questions until her craving for knowledge was satisfied.

Padolina was later sent to her first-ever formal training on rice breeding conducted by IRRI in Laguna, participated in by world rice breeders. She re-echoed her learnings to her colleagues. The Rc 160 is just one of 20 rice varieties she developed along with other plant breeders at PhilRice.

Her goal as a breeder, who reactivated from retirement, is to help farmers realize the importance of replacing old rice varieties with superior traits.

“Fresh varieties have improved genetics based on the current conditions and future climate to ensure higher yield and productivity. They possess sturdier tolerance and resistance to abiotic and biotic reactions,” she stressed.

Augmentation strategy is now one of the norms, hence Rc 160 is being improved by re-introducing traits such as pest resistance through modern biotechnology without altering its superior grain quality.

Helping communities through rice breeding

Sharing Cabusora’s mentality, Padolina maintains that farmers can never have a single variety to plant forever. Different genes need to be infused for varieties to adapt to the challenges of drought, flooding, and diseases.

“Varietal development needs to be continuous to counter the impacts of climate change along with other challenges,” Padolina said.

Currently, she breeds for short-duration or early-maturing rice varieties that can respond to climate change and the necessity for intensified cultivation. She also develops cold-tolerant varieties for the Cordilleras. The rice plant thrives under temperatures of 18°C to 35 °C. A temperature that is too high or too low could immensely affect its fertility and productivity.

She explained that our highlands can only produce 30% of their total rice needs. Padolina devotes herself to reaching farmers even in far-flung areas, and helping them improve their productivity without displacing their culture and way of life.

“You need to help all the farmers, whether they’re small or big,” she explained.

For PhilRice breeders, the biggest challenge in rice breeding is not the breeding itself nor the time they wait for the results. It is not the repeated wading in muddy fields to select plants that exhibit the desired characteristics. It is neither the laboratory results nor the numerous certifications and examinations by quality control institutions.

The final verdict will come from the farmers themselves who will plant the new varieties, hoping that the hard work of rice breeders for more than a decade will pull up the yield and improve our farmers’ lives.

Defying time—this is the breeders’ way of serving the public.

Continuous effort

Padolina underscores that breeding remains the most cost-effective intervention to help farmers adapt to the challenges brought about by increasingly scarce resources and climate change.

The consulting breeder emphasizes the advantages of conventional methods. She advises that a rice breeder shouldn’t be confined in the laboratory. The best way of breeding is still being out in the field and seeing rice through their own eyes, together with farmers.

“We need to see the actual interaction of the crop with the environment so we can choose the best variety,” she explained.

Breeding rice is challenging; to succeed it requires patience, commitment, and a deep understanding of your plant and of the farmers who are the intended users. Nevertheless, the breeders’ shared hopes and aspirations with Filipino farmers remain certain for a rice-secure country.