Ratooning increases rice production

The local terms for rice ratooning are sagibo in Guimba and sangang-buko in Aliaga, Nueva Ecija. Sangang-buko literally translates as “that which branched out (sanga) from the joint (buko),” providing an accurate depiction of the rice ratooning process. Despite its cultural significance, academic literature focusing on the practices contextualized in these two towns is scarce. Some studies, such as the research by Gajete et al. (2018), explore the potentials of improved rice ratooning technology in rainfed rice production areas to achieve higher yields within shorter periods through prescribed nutrient application. However, fieldwork suggests that rainfed ratooning is generally unpopular among local farmers. Nevertheless, farmers “claim” that ratoon rice has better eating quality than that of the main crop because it is chemical-free…

What drives rice production growth in PH?

Producing enough rice to feed the growing Filipino population remains a daunting challenge. Population increased rapidly from 92 million in 2010 to 109 million in 2022, confounded by rising per capita net rice disposable consumption, from 114 kg/year to 136 kg/year during the same decade. Although milled rice production grew substantially, from 10.3 million metric tons (Mt) to 12.9 million Mt, it was not enough to cater to the increasing demand. Moreover, increasing production has been slowed down by several challenges, such as climate change, biotic factors, biodiversity loss, small farm sizes, aging farmers, slow diffusion and adoption of technologies, slow progress in farm modernization, and weak value chain development. Nonetheless, being our staple food, the struggle to seek alternative strategies to augment rice production continues to be our top priority…

What contributes to palay farmgate price formation?

Palay farmgate price is a key consideration in a farmer’s decision to plant: a high price pushes them to cultivate rice in larger areas; a low price could make them plant other crops. Consequently, the rise and fall in farmgate price heavily influences changes in wholesale and retail prices of milled rice, compromising the affordability of rice among consumers. With rice eating up the largest share in food expenditures, it has an inflationary effect that impacts the whole economy. This underscores the importance of understanding the formation of palay prices. Even so, the movements in farmgate prices frequently remain a paradox…

Crop diversification mitigates climate-change impacts

Climate change refers to the gradual rise in global temperatures and adjustments in weather patterns. This is primarily caused by greenhouse gases (GHG) released into the atmosphere either by natural forces, such as volcanic eruptions, or human activities, such as fossil fuels burning. GHG are said to envelop the earth’s surface preventing the sun’s heat from escaping, thus leading to global warming (United Nations, n.d.). This means more warmer days, extreme droughts, water scarcity, rise in sea water levels, heavier rainfall causing floods, more frequent devastating storms, among other climate hazards.

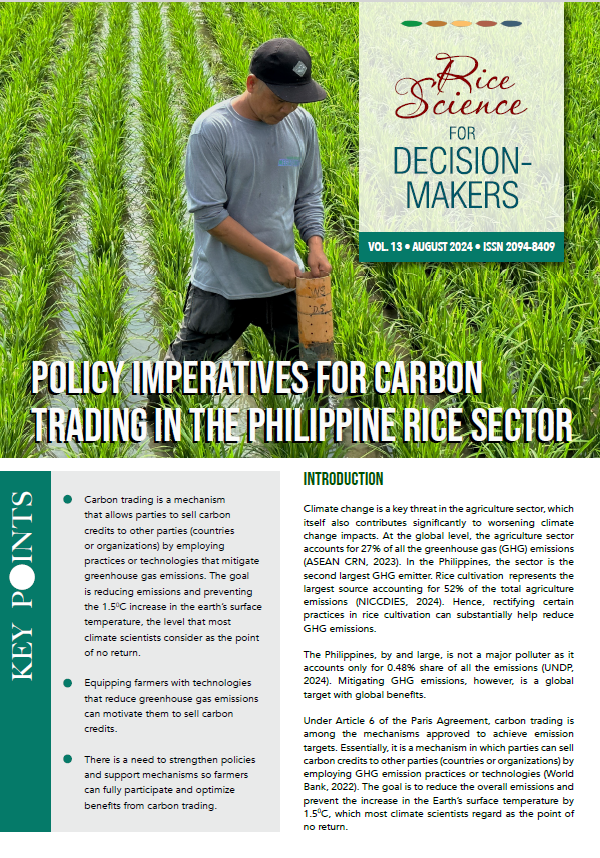

Policy imperatives for carbon trading in the Philippine rice sector

Climate change is a key threat in the agriculture sector, which itself also contributes significantly to worsening climate change impacts. At the global level, the agriculture sector accounts for 27% of all the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (ASEAN CRN, 2023). In the Philippines, the sector is the second largest GHG emitter. Rice cultivation represents the largest source accounting for 52% of the total agriculture emissions (NICCDIES, 2024). Hence, rectifying certain practices in rice cultivation can substantially help reduce GHG emissions.

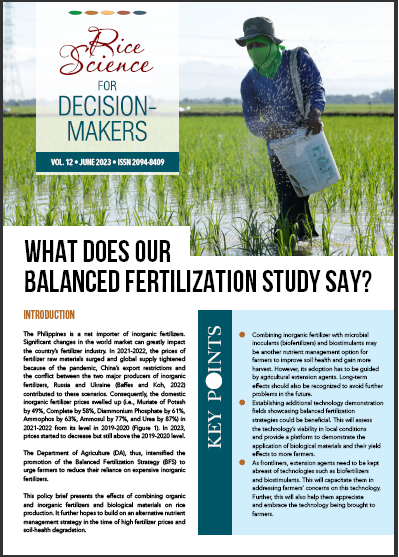

What does our balanced fertilization study say?

The Philippines is a net importer of inorganic fertilizers. Significant changes in the world market can greatly impact the country’s fertilizer industry. In 2021-2022, the prices of fertilizer raw materials surged and global supply tightened because of the pandemic, China’s export restrictions and the conflict between the two major producers of inorganic fertilizers, Russia and Ukraine (Baffes and Koh, 2022) contributed to these scenarios. Consequently, the domestic inorganic fertilizer prices swelled up (i.e., Muriate of Potash by 49%, Complete by 58%, Diammonium Phosphate by 61%, Ammophos by 63%, Ammosul by 77%, and Urea by 87%) in 2021-2022 from its level in 2019-2020 (Figure 1). In 2023, prices started to decrease but still above the 2019-2020 level.

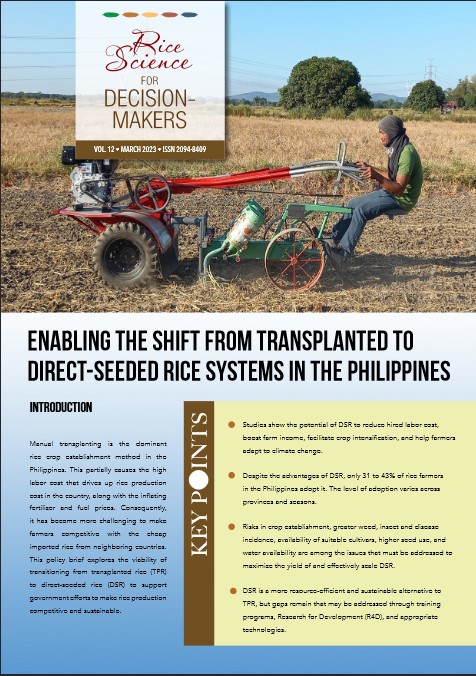

Enabling the shift from transplanted to direct-seeded rice systems in the Philippines

Manual transplanting is the dominant rice crop establishment method in the Philippines. This partially causes the high labor cost that drives up rice production cost in the country, along with the inflating fertilizer and fuel prices. Consequently, it has become more challenging to make farmers competitive with the cheap imported rice from neighboring countries. This policy brief explores the viability of transitioning from transplanted rice (TPR) to direct-seeded rice (DSR) to support government efforts to make rice production competitive and sustainable.

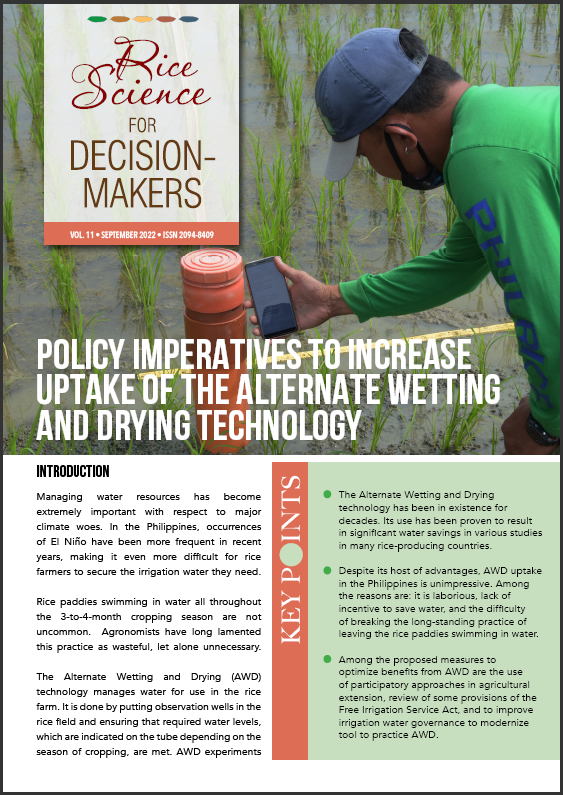

Policy imperatives to increase uptake of the Alternate Wetting & Drying Technology

Managing water resources has become extremely important with respect to major climate woes. In the Philippines, occurrences of El Niño have been more frequent in recent years, making it even more difficult for rice farmers to secure the irrigation water they need.

Reinforcing right E-A-T for improved fertilizer application

What is right E-A-T of fertilizer application?

Right E-A-T refers to the correct nutrient Element,

Amount, and Timing of fertilizer application. It is the

essence of PalayCheck’s Key Check 5, which is about nu-

trient management, and is embedded in the integrated

nutrient management framework (Figure 1). Key Check

5 targets sufficient nutrients during the tillering, early

panicle initiation (EPI), and flowering stages. For far-

mers to know the right element and amount of fertilizer

to apply, Key Check 5 recommends the use of visual

observation coupled with nutrient diagnostic and decision

support tools such as the Leaf Color Chart (LCC), Minus-

One-Element Technique (MOET), Nutrient-Omission-

Plot Technique (NOPT), and the Rice Crop Manager

(RCM). The timing of fertilizer application depends on

the critical stages at which each nutrient is needed.

How may we help rice farmers in drought-prone areas?

Over time, it is known that frequency of different climate change impacts like drought will continue to increase (IPCC, 2012; Cai et al., 2018; Gabriel et al., 2021). Drought causes major damage in agriculture. In rice cultivation, certain farmers had been reported ending up with zero yield (Pandey, Bhandari, Ding, et al., 2007)

Are there good reasons to push for Varmix in unfavorable rice-growing areas in the Philippines?

What is varmix?

Varietal Mixture (VarMix) is a mixture of seeds of selected varieties with closely similar agronomic traits but with genetic dissimilarities. Agronomic traits pertain to maturity, height, and grain size, and shape, while genetic dissimilarities refer to the distinct genetic makeup of a rice variety. These varieties have diverse functions to lessen the effects of both biotic (e.g. pest and diseases) and abiotic (e.g. water) stresses (Tooker & Frank, 2012; Barot et al., 2017; Montazeaud et al., 2017)

Digital Agriculture – How can we make it work?

There is a need to devise strategies to ensure

that farmers suffering from information and

communications technology (ICT) anxiety may be

able to optimize the benefits of ICTs. ICT anxiety is

the feeling of discomfort when in front of ICTs (e.g.

computers). It is common among old people, which

typifies the majority of farmers in the Philippines.

Results of the 2016-2017 Rice-Based Farm Households Survey note that while ICT access of farmers is high at 93%, the percentage of those who use ICTs as tools in their rice cultivation is only 31%.

The Infomediary Campaign, a youth engagement in agriculture initiative of DA-PhilRice, was implemented to help address ICT anxiety among farmers. The idea was for high school students coming from rice-farming communities to help access information for farmers.

The Campaign resulted in close to 20,000

inquiries sent by more than 4,000 student-texters

(infomediaries) nationwide. Instances of technology

adoption were noted in the project sites.

Farmers increase yield, adapt to climate change through community action

A project in Aurora Province from 2012 to 2014 saw that challenges of climate change and rice production are best addressed together by the community.

Farmers participating in the project who agreed to practice synchronous planting were rewarded with less pest damage and more yield.

Passing ordinances incentivizing collective action in employing yield-enhancing practices like synchronous rice planting is in the right direction if the aim is to increase yield and enhance farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change impacts.

How the tax reform for acceleration and inclusion law impact rice farmers

Farmers who depend on pumps for irrigation water suffer

from the increased fuel prices. Their fuel consumption

accounts for some 30% of their total production cost.

TRAIN increases the production cost of pump-dependent

farmers by 50 centavos for every kilogram of palay

produced, which diminishes their income by 10%.

Mechanization does not significantly increase farm

fuel cost.

To cushion the ill effects of TRAIN on rice farming,

pump-dependent farmers have to continue using yieldenhancing

technologies, reduce harvest losses through

mechanization, and adopt water-saving technologies

like Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD). Government

programs that promote and/or provide these

technologies will be helpful.

The government has to hasten the completion of projects

on large-scale irrigation systems as these will help farmers

access cheaper and reliable water.

Is hybrid rice worth investing in?

Rice prices are expected to drop when trade

protection shall have finally been relaxed

in compliance with our international trade

agreements. To remain in the market, farmers

have to strategize on how to compete in terms

of quality and price of their products. This policy

brief tackles Hybrid Rice as one of the ways to help

farmers survive in a market with tight competition,

especially with cheaper imported rice. It discusses

implications of hybrid rice on the country’s total

rice supply and on farmers’ competitiveness;

identifies the factors that make farmers adopt

hybrid rice; and presents possible steps to hasten

its adoption.

Mechanizing postharvest work enhances farmers’ competitiveness

The Philippines (PH) currently adopts tariff and quantitative restriction (QR) as trade protection for rice. Tariffs are taxes imposed on traded products; QRs limit the volume of imported rice allowed into the country. Trade protection regulates the influx of cheaper imported rice in the local market, and shields local farmers and traders from superior competition. If government would remove QR, local rice prices would drop (Litonjua and Bordey, 2014; Bordey et al., 2016) in favor of consumers but to the detriment of farmers.

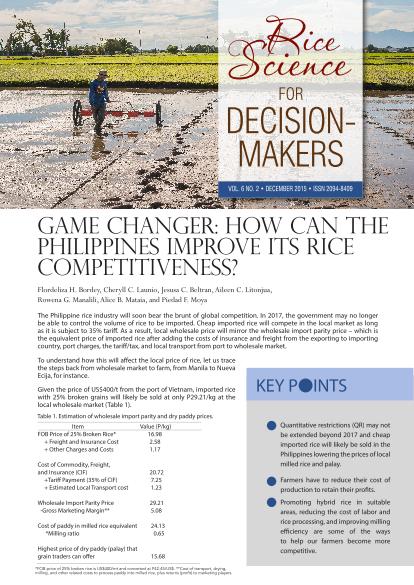

Game changer: How can the Philippines improve its rice competitiveness? – December 2015

The Philippine rice industry will soon bear the brunt of global competition. In 2017, the government may no longer

be able to control the volume of rice to be imported. Cheap imported rice will compete in the local market as long

as it is subject to 35% tariff. As a result, local wholesale price will mirror the wholesale import parity price – which is

the equivalent price of imported rice after adding the costs of insurance and freight from the exporting to importing

country, port charges, the tariff/tax, and local transport from port to wholesale market.

Game changer: Is PH rice ready to compete at least regionally? – November 2015

Zero rice importation or self-sufficiency has always been the elusive goal of Philippine agriculture policies regardless of political dispensation. Any inferior goal is unpatriotic and criticized as a failure of the government and the nation as a whole. Figure 1 shows the historical net rice imports of the Philippines.

How can rice trade liberalization affect producers and consumers? – September 2014

Tariffs and quantitative restrictions (QR) are used to control the entry of imported rice in the country. Tariffs are taxes imposed on traded products; QRs are measures such as quotas and bans that limit the volume of rice allowed into the country.

Combining organic and inorganic fertilizers; recommended practice for sustaining rice yield – June 2012

Organic fertilizer is made of animal or plant biomass that has completely decomposed until the original material has become soil-like in texture. Biofertilizers, or microbial fertilizers, compost activators, inoculums are commonly classified as organic fertilizers, but they are either soil conditioners or growth enhancers.